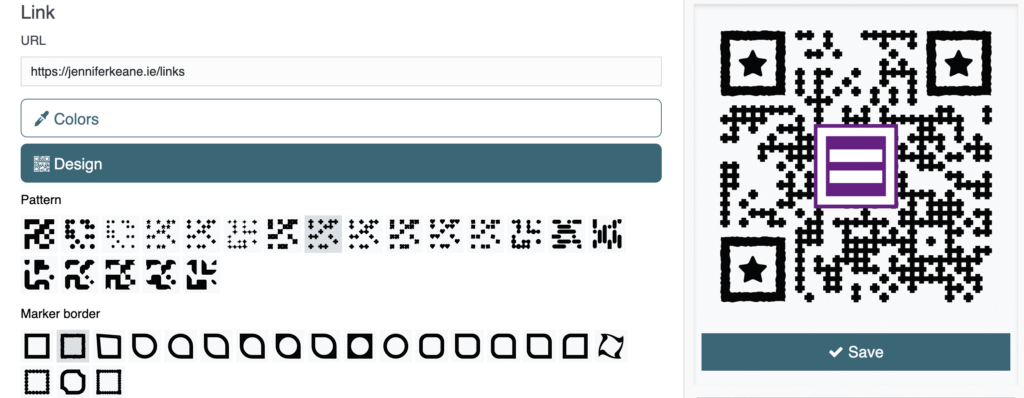

I attended a talk recently about migraine, and included in the talk was a demo and a quick blurb about a new-ish medical device to potentially treat migraine and other headache conditions (an external vagus nerve stimulation device, for the curious). It seems an interesting development, since previous incarnations of the same required surgery and an implanted device, but when I did a little more investigating I was disappointed to discover that the device operates on a subscription model. Every 93 days, you have to buy a new card to “activate” the device and make it work for another block of time. It’s not to do with the monitoring of a patient, or wanting a clinical touchpoint every 3 months or so (because you can also opt for the very expensive “36 months in one go” option), it is simply a business model – sell a device that becomes an expensive paperweight if a subscription is not maintained.

Over the last few days, it has prompted me to think about the landscape we are building for ourselves – one populated with smart devices, subscription devices, as well as an increasing cohort of medical devices – what it will look like in the future, what we owe to customers of these devices if we are involved in making them, and ultimately, what we owe to each other.

Subscription Business Models

Subscription-based business models are nothing new – chances are you’re paying for at least one subscription service yourself. For many businesses they are an attractive choice as they mean a continuous revenue stream, a constant inflow of cash you can plan around, rather than one big bang purchase and then a drought. And lots of people are fine with paying for subscription models, even if they don’t love them, but what if we’re talking about more than just streaming music or paying monthly for Photoshop? What if instead of software or an intangible thing, we’re talking about physical devices?

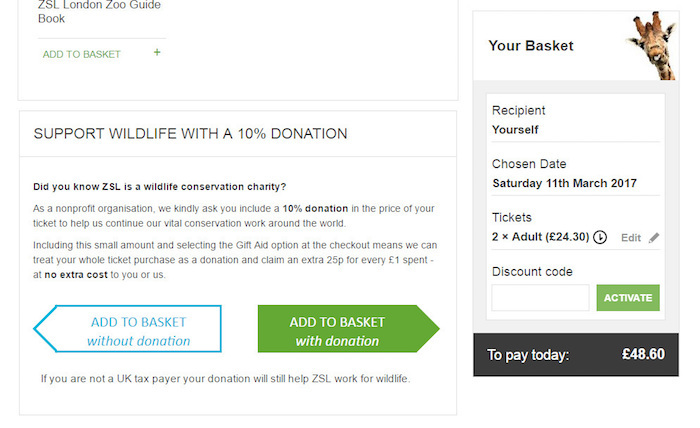

Physical devices with a subscription model aren’t exactly new, and they’ve had their problems – Peloton came under fire in 2021 after it seemed to release an update that forced a subscription onto its users and rendered its treadmills useless without one. BMW were recently the subject of much negative press for their subscription model heated seats – shipping cars with the physical equipment needed to heat the seats, but locking it behind a subscription paywall. And HP Instant Ink subscribers found that once they cancelled the Instant Ink service, the ink left in their cartridges stopped working, even though it was still sitting their in their printers.

This is all very annoying, but mostly you could argue the above are luxuries – your seats aren’t heated, your day still goes on. But these are not the only kinds of devices that, increasingly, are coming with subscriptions.

What happens when your bionic eyes stop working?

The merging of technology and medicine is, to a certain extent, inevitable. People have unofficially relied on technology to supplement and assist with medical issues for a long time now (such as those with diabetes hacking pumps to essentially make artificial pancreas, a process known as looping, or people with vision impairments using apps to see through the camera, receiving audio descriptions), and as time goes on, manufacturers are joining the market with “official” solutions. There is huge potential to make lives better with assistive technologies, by automating processes that were manual or artificially replacing senses to name just two examples. Often these developments have been lauded as the “way of the future” and a huge step forward for humanity, but what happens when the initial shine passes?

A CNN article from 2009 speaks about Barbara Campbell, a woman who was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa – a condition which gradually robbed her of her sight. In 2009, she was participating in an FDA approved study of an artificial retina – a technological solution to her impaired vision, a microchip to help her see again by stimulating the retina electrically in the way that light should be. Combined with a pair of sunglasses and a camera to capture the world around her, the devices allowed her to see again, with her interpretation of the new signals improving all the time. By all accounts, it’s a dream scenario – technology that is really doing good and changing someone’s life for the better.

Now, in 2022, things have changed. In 2020, the company that manufactured these implants had financial difficulty. Their CEO left the company, employees were laid off, and when asked about their ongoing support, Second Sight told IEEE Spectrum that the layoffs meant it “was unable to continue the previous level of support and communication for Argus II centers and users.” Around 350 patients worldwide have some form of Second Sight’s implants, and as the company wound down operations, it told none of them. A limited supply of VPU (video processing units) and glasses are available for repairs or replacements, and when those are gone, patients are figuratively and literally in the dark.

Barbara Campbell was in a NYC subway station changing trains when her implant beeped three times, and then stopped working for good.

Now patients are left with incredibly difficult decisions. Do they continue to rely on a technology which changed their lives but which has been deemed obsolete by the company, that may cause problems with procedures such as MRIs, with no support or repair going forward? Or do they undergo a potentially painful surgery to remove the devices, accruing more medical costs and removing what sight they have gained? Do they wait until the implant fails to remove it, or do they remove it now, gambling on whether it might continue working for many years? Do they walk around for the rest of their lives with obsolete, non-functional technology implanted in them, waiting for the day it fails and replacement parts can no longer be found?

Meanwhile, Second Sight has moved on, promising to invest in continuing medical trials for Orion, their new brain implant (also to restore vision) for which it received NIH funding. Second Sight are also proposing a merger with an biopharmaceutical company called Nano Precision Medical (NPM). None of Second Sight’s executives will be on the leadership team of the new company. Will those who participated in the Orion trials to date continue to receive support in the future, or even after this merger?

IEEE Spectrum have written a comprehensive and damning article examining the paths taken by Second Sight, piecing together the story though talking to patients, former doctors and employees, etc. and although it’s clear that Strickland and Harris know more about this than anyone, even they can’t get a good answer from the companies about what happens now to those who relied on the technology. Second Sight themselves don’t have a good answer.

Subscription Paperweights

Second Sight’s bionic eyes didn’t come with a subscription, but they should have come with a duty of care that meant their patients never had to worry about their sight permanently disappearing due to a bug that no one would ever fix or a wire failing. And while bionic eyes are an extreme example of medical tech, they’re an excellent example of the pitfalls that this new cohort of subscription-locked medical devices may leave patients in.

Lets return for a moment to the device that started me down this line of thought – the external vagus nerve stimulator. I have had a difficult personal journey with migraine treatment. I have tried many different drug-based therapies, acute and daily preventatives, and have yet to find one which has been particularly effective or that didn’t come with intolerable side effects. I am now at a point where the options available to me are specialist meds available only with neurologist consults and special forms and exceptions, or the new and exciting world of migraine medtech devices. And the idea of a pocketable device that I use maybe twice a day, perhaps again if I am experiencing an attack, is appealing. With fewer side effects, no horrible slow taper off a non-working med, and let’s be honest, a cool cyberpunk vibe, I’m more than willing to give this kind of thing a try. Or I would be, if it wasn’t tied to a subscription model.

Because I can’t help but think of Barbara, and the day her eyes stopped. And I can’t help but think about how many companies fail, suddenly, overnight, with no grand plan for a future or a graceful wind down. And I can’t help but worry that I might finally find something to sooth this terrible pain in my head, to give me my life back, only to have it all disappear a year down the line because the company fails and I have no one to renew a subscription with, and my wonder-device becomes an expensive and useless piece of e-waste.

The decision to add a subscription model to a device such as this is financial, not medical. Internal implantable vagus nerve stimulators already exist for migraine and other conditions, and you don’t renew those by tapping a subscription card. This is a decision motivated by revenue stream.

To whom do you have a duty of care?

The migraine vagus nerve device is not alone. When I shared the news about this device with a friend, she told me that her consultant had been surprised to find that her smartphone-linked peak flow meter did not have a subscription attached. Subscription medtech devices have become a norm without many noticing, because many people do not (and may never) rely on devices like this to exist.

The easy argument here is that companies deserve to recoup their expenses – they invested in the devices, in their testing and development, in their production. If the devices are certified by medical testing boards, if they underwent clinical trials, there is significant costs associated with that, and given the potential market share of some of these devices, if they simply sell them for a one-time somewhat affordable cost, they will never see a return on their investment. This, in turn, will discourage others from developing similar devices. And look, it’s hard to refute that because it is true – it is expensive to do all of these things, and a company will find it very hard to continue existing if they simply sell a handful of devices each year and have no returning revenue stream. If this were purely about the numbers, this would be the last you’d hear from me on the topic. But it’s not.

If you develop a smart plug with a subscription model, and your company fails, this is bad news for smart plug owners, but a replacement exists. A world of replacements, in fact. And the option to simply unplug the smart device and continue without it is easy, and without major consequence. The ethical consequences are low. But developing a medtech device is simply not the same. It is about so much more than the numbers. This is not about whether someone can stream the latest Adele album, this is about ongoing health and in some cases lives, and this is an area of tech that should come with a higher burden than a smart doorbell or a plug.

When you make any sort of business plan, you’ll consider your investors, your shareholders, perhaps your staff, and certainly your own financial health, but when it comes to medtech, these aren’t the only groups of people to whom you should owe your care and consideration. Your circle of interested parties extends to people who may rely on your device for their health, for their lives, beyond just a simple interest or desire to have a product that works. Simply put, is your duty of care to your shareholders, or to your patients?

What do we owe to each other

Do you owe the same duty of care to a smart doorbell owner as to a smart heart monitor owner? Who will face a tougher consequence if your company fails without warning?

Second Sight took grants and funding to continue developing and trialling their brain implant while they quietly shelved the products they had already implanted in real patients – is this ethical? Is it right? How can anyone trust their new implant, knowing how patients using their previous implant were treated and the position they were left in? And is it right to continue to grant funding to this research?

Companies right now are developing devices which lock people into a subscription model that will fail if and when the company fails, at a time when we are all concerned about the impact of technology on the environment, conscious of e-waste, and trying to reduce our carbon footprint. They are developing devices that work for 12 months and then must be replaced with new ones. Is it right to develop throwaway medical devices that stop working simply so that you can lock people into a renewing subscription/purchase model?

It is undeniable that technology can help where current medical options have failed. We have already seen this with devices that are on the market, and with new devices that arrive. We should want to pursue these avenues, to make lives better and easier for those who need help. We should fund these technologies, spur on innovation and development in these areas, and help everyone to reach their fullest potential.

But we owe it to each other to push for better while we do. To push back on devices that will fail because someone’s payment bounces. To push back on devices that only have subscription models and no option to purchase outright. To push for higher standards of care, better long term support and repair plans which can exist even if the company fails. To push for companies to be held to these standards and more, even if it makes things more difficult for them. And to push companies to keep developing, even with these standards in place, to keep developing even though it is hard.

We deserve a duty of care that extends not just to lifetime of device, but the lifetime of a patient.

This isn’t just about home security, or smart lights – this is people’s health, their lives. The duty of care should be higher, the ethical burden stronger. We owe it to each other to not allow this world to become one where vision and pain relief and continued survival depends on whether or not you can pay a subscription.