I want to talk about ethics, diversity, and inclusion in engineering, how we often miss the mark, the impact that has, and the changes we can make to truly bring change from the inside out. My goal is to explain why this is important, and show you some examples where a simple decision resulted in a barrier for someone.

Why does this matter? Why is it important to be thinking about ethics when we’re developing software? Because software (apps, websites, etc) is becoming the fabric of society – increasingly it is involved in everything we do, from shopping for groceries to online banking to socialising. There is very little in our lives now that is not touched, in some way, by software.

As we integrate software into more and more areas of our lives, we are also increasingly turning to automated and predictive solutions to perform tasks that were once manual. We are asking computers to do “human” things, more open-ended “thinking” tasks, but computers aren’t human. Most people, when they think of AI, think of something like Data from Star Trek. The reality of AI however is that we have “narrow” AI – models which are trained to do a specific thing and that thing only. These models are unable to add context to their decisions, to take additional factors into account if they are not in the data model, or even to question their own biases. It takes in data, and returns data.

Lastly, we often spend a lot of time discussing how we will implement something, but perhaps not as much time discussing whether we should implement something. We know that it is possible to build software which will have in-app purchases, and that it’s possible to incentivise those in-app purchases so that they are very attractive to app users. We have seen that it is possible for people to target this marketing towards children – answering the “can”, but not addressing the “should we?”

When I say we should consider the “should” rather than the “can”, what do I really mean? I’m going to show some real world examples where decisions made during product design ripple out into the world with negative effects. In each of these examples, there probably wasn’t malicious intent, but the result is the same – a barrier for an individual. Most of these examples are not due to programming errors, but by (poor) design.

Have you ever accidentally subscribed to Amazon Prime?

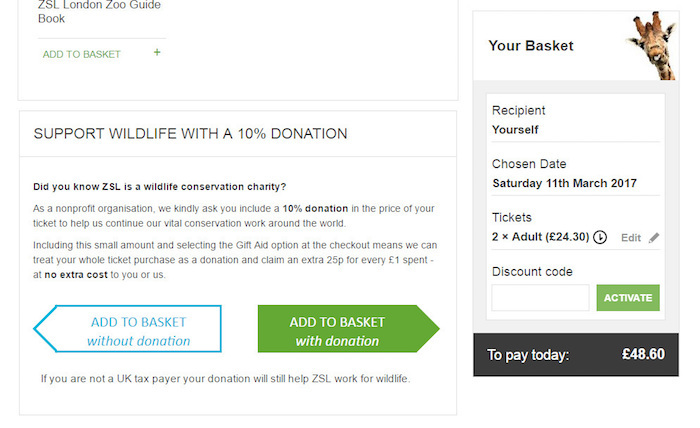

Do you know what a dark UX pattern is? You’ve probably encountered one, even if you’ve never heard the term. Have you ever accidentally opted-in to something you meant to deselect, found an extra charge on a bill that you didn’t even realise you had signed up for? Have you ever tried to cancel a service, only to discover that the button to “cancel” is hidden below confusing text, or the button that looks like a cancel button actually signs you up for even longer? How about accidentally signing up to Amazon Prime when you just wanted to order a book? These are dark UX patterns – design changes that are designed to trick the user. They can be beneficial for the person who implements them, but usually to the detriment of the user. In the image above, we see two buttons to add your tickets to the basked. An optional donation can be added with the tickets, but the option to add without donation is much harder to read. It also points backwards, implying visually that this would bring you back a step. Is the value of this donation worth the confusion? Is this ethical? Should a donation be opt-out or opt-in?

Have you ever been told that your name is incorrect?

Your name is one of the first things you say to people you meet, it is how you present yourself to the world. It is personal and special. But what if you are told that your name is incorrect due to lazy or thoughtless programming every time you try to book an airline ticket, access banking, healthcare, or any number of services online? A multitude of online forms fail to support diacritical marks, or declare that names are too short or too long based on simple biases and the incorrect assumption that everyone has a first and last name that looks like our own. Instead, we should be asking – do we need to separate people’s names? Why do you need a “first” and “last” name? Could we simply have a field which would accommodate a user’s name, whatever form that takes, and then another which asks what they prefer to be called?

Let’s talk about everyday barriers

We’ve never been more aware of handwashing, and a lot of places are using automatic soap or hand sanitiser dispensers to ensure that people stay safe without having to touch surfaces. But what if they don’t work for you? Many soap dispensers use near-infrared technology, which sends out invisible light from an infrared LED bulb for hands to reflect the light back to a sensor. The reason the soap doesn’t just spill out all day is because the hand acts to bounce back the light and close the circuit, activating the soap dispenser. If your hand has darker skin, and actually absorbs that light instead, then the sensor will never trigger. Who tests these dispensers? Did a diverse team develop these or consider their installation?

Why don’t zoom backgrounds work for me?

If you’re like me, you’ve been using meeting backgrounds either to have some fun or to hide untidy mixed working spaces while adapting to working from home during this past year. When a faculty member asked Colin Madland why the fancy Zoom backgrounds didn’t work for him, it didn’t take too long to debug. Zoom’s facial detection model simply failed to detect his face. If you train your facial detection models using data that isn’t diverse, you will release software that doesn’t work for lots of faces. This is a long running problem in tech, and companies are just not addressing it.

Why can’t I complain about it on twitter?

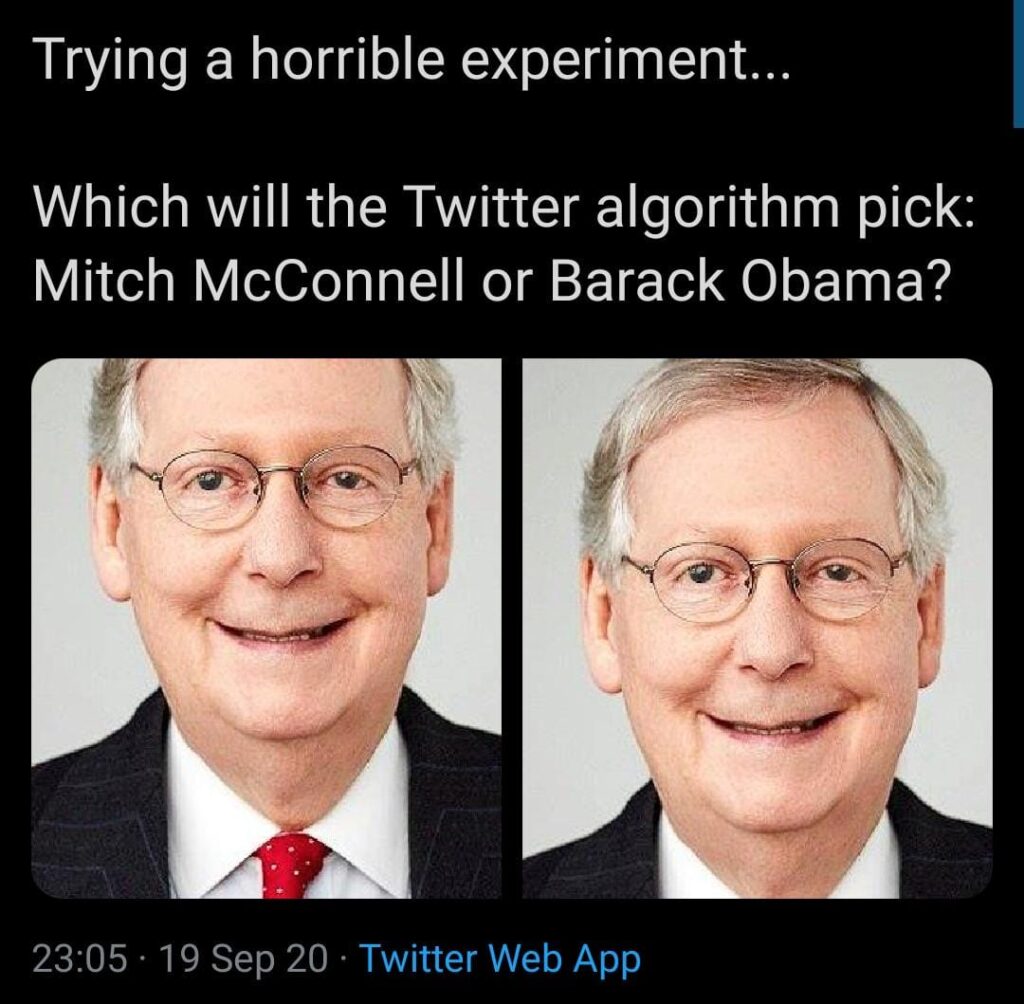

When Colin tweeted about this experience, he noticed something interesting with Twitter’s auto-cropping for mobile. Twitter crops photos when you view them on a phone, because a large image won’t fit on screen. They developed a smart cropping algorithm which attempted to find the “salient” part of an image, so that it would crop to an interesting part that would encourage users to click and expand, instead of cropping to a random corner which may or may not contain the subject. Why did twitter decide that Colin’s face was more “salient” than his colleague’s? It could be down to the training data for their model, once again – they used a dataset of eye tracking information, training their model to look for the kinds of things in an image that people look at when they look at an image. Were the photos tested diverse? Were the participants diverse? Do people just track to “bright” things on a screen. It certainly seems there was a gap and the end result is insulting. Users tested the algorithm too, placing white and black faces on opposite ends of an image to see how twitter would crop them. The results speak for themselves. Twitter said they tested for bias before shipping the model….but how?

This impacts more than social media. It could impact your health

Pulse oximeters measure oxygen saturation. If you’ve ever stayed in a hospital chances are you’ve had one clamped to your finger. They use light penetration to measure oxygen saturation, and they often do not work as well on darker skin. This has come to particular prominence during the pandemic, because hospitals overwhelmed with patients started spotting differences in oxygen levels reported by bloodwork and by the pulse ox. This could impact clinical treatment decisions, as they report higher oxygen saturations than are actually present. This could lead to a delay in necessary clinical treatment when a patient’s o2 level drops below critical thresholds.

This could change the path your life takes

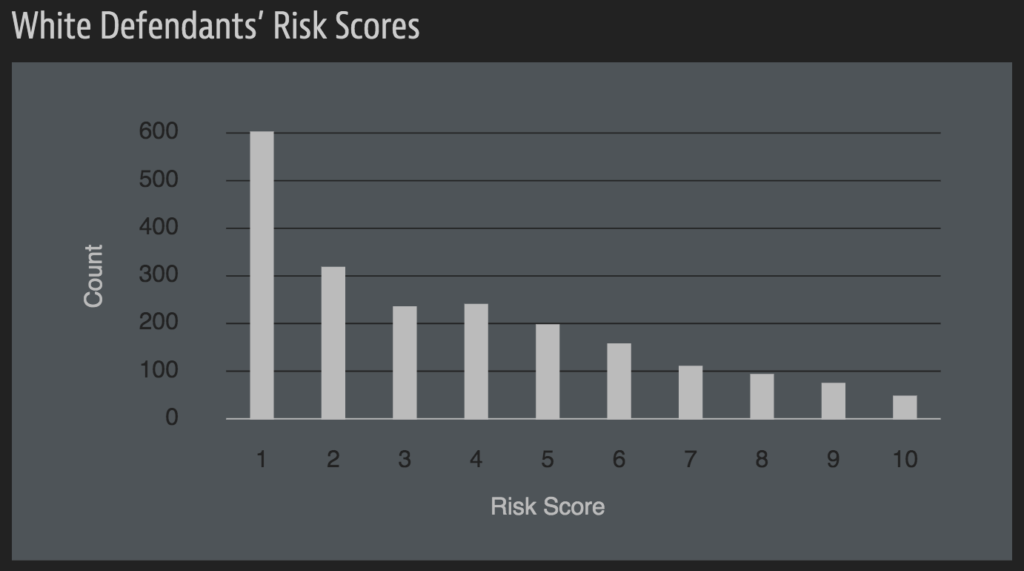

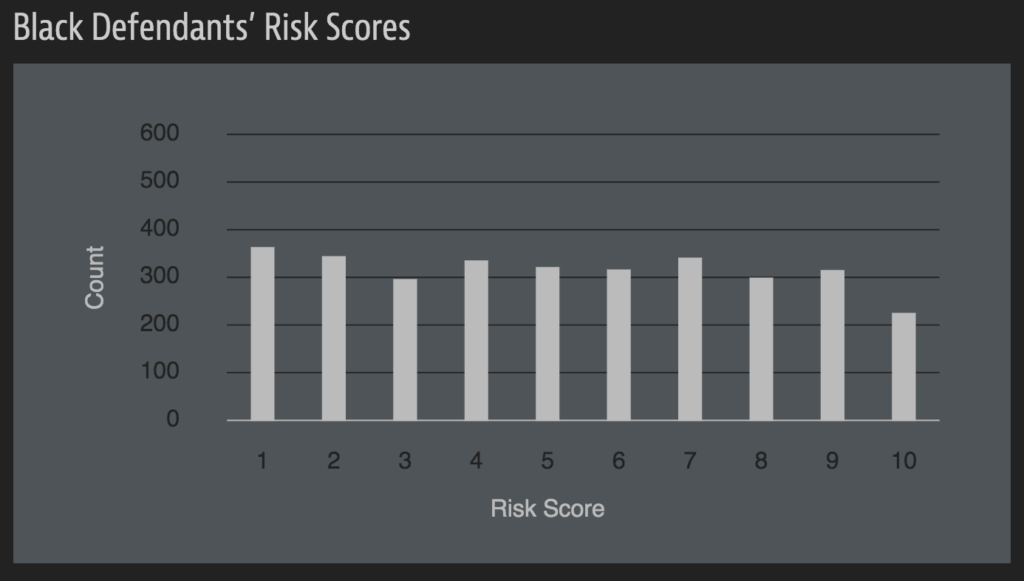

COMPAS is an algorithm widely used in the US to guide sentencing by predicting the likelihood of a criminal reoffending. In perhaps the most notorious case of AI prejudice, in May 2016 the US news organisation ProPublica reported that COMPAS is racially biased. While COMPAS did predict reoffending with reasonable accuracy, black people were twice as likely to be rated a higher risk but not actually reoffend. The graphs show that risk scores are very far from normal distribution – they are skewed heavily towards low risk for white defendants. In multiple real life examples from the ProPublica analysis, the black defendant was rated as a higher risk, despite fewer previous offences, and in both cases that individual did not reoffend, although the “lower risk” defendant did.

And these are, sadly, just selected examples. There are many, many, many more.

Clang, clang, clang went the trolley

As we come to the end of the real world examples, I want to leave you with a hypothetical that is becoming reality just a little bit too fast. Something that many people are excited about is the advent of self-driving cars. These cars will avoid crashes and keep drivers safe and allow us to do other things with our commute. But….

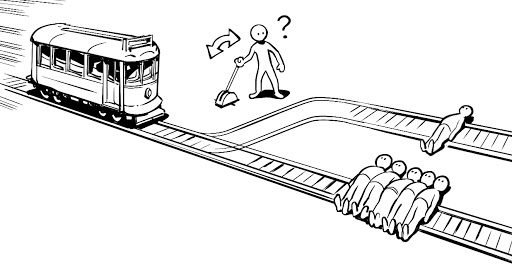

Have you ever heard of the trolley problem? It’s a well known simple question that is often used to explore different ethical beliefs. In case you aren’t familiar with this yet, the picture above is a fair summary. Imagine you are walking along and you see a trolley, out of control, speeding down the tracks. Ahead, on the tracks, there are five people tied up and unable to move. The trolley is headed straight for them. You are standing some distance off in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull this lever, the trolley will switch to a different set of tracks. However, you notice that there is one person on the side track. You have two options:

- Do nothing and allow the trolley to kill the five people on the main track.

- Pull the lever, diverting the trolley onto the side track where it will kill one person.

What is the right thing to do?

The tricky thing is that there are numerous ways to try and decide what is right, and there isn’t really a right answer. As humans we can perhaps use more about the context to aid us in a decision, and we can take in all of the information about the situation even if we have not encountered the situation before, but even then we still can’t always come to a right answer. So how do we expect a smart car to decide?

While we might not see a real life trolley problem in our lifetimes, the push towards self driving cars will almost certainly see a car presented with variations on this problem – in avoiding an accident, does the car swerve to hit one pedestrian to save five? Does it not swerve at all, to preserve the life of the driver? Given what we know about recognition software as it currently stands, will it accurately recognise every pedestrian?

How will the car decide? And who is responsible for the decision that it makes? The company? The programmer who implemented the algorithm?

I don’t have an answer for this one, and I’m not sure that anyone does. But there is a lot that we can do to action inclusive and diverse programming in our jobs, every single day, so that we remove the real barriers that I’ve already shown.

What can we do?

First and foremost, diversity starts from the very bottom up. We need to be really inclusive in our design – think about everyone who will use what you make and how they will use it, and really think beyond your own experience.

Make decisions thoughtfully – many of the examples I’ve shown weren’t created with malicious intent, but they still hurt, dehumanised, or impaired people. Sometimes there isn’t going to be a simple answer, sometimes you will need to have a form with “first name” and “last name”, but we can make these decisions thoughtfully. We can choose to not “go with the default” and consider the impact of our decisions beyond our own office.

Garbage in, garbage out – if you are using a dataset, consider where it came from. Is it a good representative set? Is your data building bias into the system, or is it representative of all of our customers?

Inclusive hiring – when many diverse voices can speak, we spot more of these problems, and some of them won’t make it out the door. Diverse teams bring diverse life experiences to the table, and show us the different ways our “defaults” may be leaving people out in the cold.

Learn more – In the coming days and weeks, I’ll be sharing more links and some deep dives into the topics I’ve raised above, because there is so much more to say on each of them. I’m going to try and share as many resources and expert voices as I can on these topics, so that we can all try to make what we make better.